When it comes to banning certain plays from being staged in Birmingham theatres, one immediately recalls the infamous official state control over theatre, which required all plays to be licensed by the Lord Chamberlain’s Office. In this way, the government ensured compliance with public morality and political correctness by banning or censoring content related to sex, profanity and the royal family.

This rule was abolished by the Theatre Act, which came into force only in 1968, putting an end to a system that had existed for more than a century. Playwrights occasionally fought against censorship, lawyers supported it for legal protection, but changing social attitudes and pressure from artists led to theatres being allowed to follow common law. Read about the peculiarities of theatre censorship in Birmingham and how it was fought here: birmingham-trend.com.

Between the national context and local specifics

Throughout most of its history, British theatre has developed under the close and often very restrictive supervision of censorship. And although Birmingham, the UK’s second-largest city and an important industrial and cultural centre, never had its own official system of theatre censorship. Its role in the history of conflicts between the dramatic arts and institutional prohibitions is far from minor. On the contrary, the city played an almost pivotal role in this confrontation. This was particularly evident in the tension between art, politics, and morality.

Until 1968, any play intended for public performance in England had to obtain permission from the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, the institution responsible for controlling the content of theatrical productions. This prior censorship was officially intended to protect public morality and social order, but in reality it also served to neutralise radical political statements and criticism of religion, the monarchy or the class structure.

The bans were not specific to English cities, meaning that when a play was rejected by the Lord Chamberlain, it was banned everywhere, including Birmingham. However, it was the regional theatres, which were more daring than those in the West End, that often attempted to push these boundaries, turning some cities into hotbeds of cultural resistance.

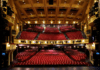

Therefore, in the 20th century, Birmingham became a city deeply marked by social realities, namely industrialisation, the working class, trade union struggles, immigration and cultural diversity. This configuration also had a significant impact on its theatre. For example, the Birmingham Repertory Theatre, founded in 1913, quickly gained a reputation as a venue willing to stage contemporary, socially engaged and sometimes controversial texts.

In this context, Birmingham was not so much a place of direct censorship as a space of confrontation between artistic ambitions and restrictions imposed by the state, local authorities or state sponsors. Debates surrounding certain plays took on particular significance here, as they resonated with the realities of local audiences’ lives.

Forbidden George Bernard Shaw

The most symbolic example of British theatrical censorship remains George Bernard Shaw. His play Mrs Warren’s Profession, written in 1893, was banned for decades because of its central theme — prostitution and the moral hypocrisy of Victorian society. Although Shaw was not a native of Birmingham, his works were often championed by regional theatres seeking to break the moral shackles imposed by London censorship.

The fact is that in Birmingham, as in other industrial cities of England at the time, Shaw’s ideas resonated particularly well with audiences sensitive to issues of social justice and criticism of the elites. Attempts to stage his plays were part of a broader strategy aimed at expanding the boundaries of permissible theatre.

Unlike Shaw or Edward Bond, only a few Birmingham writers had their works officially banned. However, some of them faced more subtle forms of censorship, often referred to as indirect or “soft” censorship. What is this about?

The most famous case is that of David Edgar, a Birmingham native and prominent figure in British political life. His plays, such as Destiny or Mayday, directly addressed sensitive topics, as they mentioned the far right, dealt with terrorism, featured ideological manipulation, and explored divisions in British society.

And here’s the interesting part. Formally, such works were not prohibited by law, but sometimes they provoked strong political hostility, which led to pressure on theatres, controversy in society and the media, and in some cases, financial disfavour from local authorities.

In Birmingham, these tensions reflected a broader reality. After the official abolition of censorship in 1968, control over the theatre did not disappear, but changed form. Conditional subsidies, self-censorship by artistic directors, fear of public or religious reaction — all these mechanisms could restrict the distribution of certain works without resorting to even an official ban.

The end of censorship

The abolition of official censorship thanks to the 1968 Theatre Act was a decisive turning point. In Birmingham, as in other large cities, a more experimental, political and diverse theatre emerged. However, this newfound freedom came with new responsibilities and conflicts.

For example, some plays that addressed issues of racism, immigration, religion, or gender caused local scandals. In Birmingham, a city that is a model of multiculturalism, these debates were often very heated and tense. Performances were no longer banned by the state, but they were sometimes removed from the repertoire or marginalised under pressure from community groups, suggesting that censorship could exist without clear legislative regulation.

The history of theatre censorship in Birmingham is not limited to a list of banned plays. Rather, it reflects an ongoing dialogue between theatre and society, between artistic freedom and political, moral or economic constraints. Within the framework of British national policy, the city distinguished itself by its active role in revising established norms. Birmingham not only experienced censorship, it often helped to fight it, transforming its theatre into a place of debate, resistance and cultural innovation.

Modern censorship

Nowadays, despite the 21st century, theatrical censorship still occurs in Birmingham. The last known case took place in 2004 at the Birmingham Rep, when Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti’s play Behzti was controversially cancelled.

This was facilitated by organised protests, which helped to stifle theatrical debate. The play Behzti contained scenes of rape, abuse, and murder inside a Sikh temple, which led to mass demonstrations outside the Birmingham Rep building. As a result, in the interests of public safety, the play was quickly “removed” from the repertoire.

Since then, it has been staged in France and Belgium, but apart from an unpublished reading at the Soho Theatre in 2010, it has never been performed in the UK. So, to sum up briefly, the conclusion is not very optimistic. It is clear that theatrical censorship in the UK in general, and in Birmingham in particular, may be dead, but complete freedom of speech has not yet been achieved.

Sources:

- https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2011/dec/27/c-for-censorship-a-z-modern-drama

- https://books.openedition.org/pur/45008

- https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/relationships/collections1/1968-theatre-censorship/1968-theatres-act/

- https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/culture/53893/censorship-is-back-on-the-british-stage